I cannot tell you just how annoying are the opinions of people who get all of their information from opinionated people on the internet. Or from a friend who “is a photographer”. In my years of photography I have worked with many people who want to get started in a particular area of photography and want to do so by disputing all the answers I give to their questions. While I certainly won’t claim to know everything there is to know about photography (no one knows everything there is to know about photography), I do have a lot of experience in the field (over thirty years as a professional working photographer with 35mm, medium and large format cameras and developing all of the photo lab processes except Kodachrome, plus 25 years digital imaging experience) and can back up my assertions with evidence. And I do. As a resident of the Show Me state, and the premier city of the Great American Midwest, I endeavor to actually demonstrate to skeptics the science behind my convictions. So let’s talk about light!!!

Many who are new to studio still photography will buy constant lights, such as those using compact fluorescent lamps (CFL), light emitting diodes (LEDs), or even photo flood lamps (the 500 watt are popular), rather than studio flashes for their first set of lights. Why? Because these can be the least expensive options and using a flash successfully requires a bit of learning. It is, however, a big mistake for a variety of reasons (yep, I’m a’ gonna list ‘em for ya). Constant lights, which emit light continuously rather than momentarily as does an electronic flash, are ideally suited for reading a book in a corner or making dull or misleading videos about something or other that the video maker thinks he, she or it knows everything about.

For us still photographers, however, studio strobes are ideal, and not just because I say so. Here are 5 solid reasons to go with studio strobes instead of constant lights for your still photography needs.

More light: Studio strobes put out more light than constant lights; much more light. Compared to a 1000 watt video light, for instance, a 600 Watt Second (WS) studio flash puts out 36 times more light – equivalent to 5 f stops. In first first photo below, I lit the room with a 1000 watt tungsten halogen video light bounced off the ceiling – at ISO 100, the exposure was 1/50 second at f4. In the second photo, I used a 640 watt second studio flash at full power, giving me an exposure of 1/50 second at f22.

1000 watt tungsten halogen lamp - 1/50th second at f4, ISO 100

640 watt second studio flash - 1/125th second at f22 ISO 100

But there is another advantage of using studio flashes. The brief duration of the electronic flash (the one I was using here has a maximum duration of about 1/600 second) means you can shoot at your cameras’s maximum flash synchronization shutter speed, which in my case is 1/200 second. That’s ¼ the time of the exposure with the tungsten light, meaning a difference of 2 more f-stops for a total of 7 f-stops. That’s a difference of 128 times – more than 2 orders of magnitude. And, in case you’re not getting the point here, that’s a BIG difference.

A difference in brightness this great makes it easy to light great big groups of people (the biggest group I’ve ever photographed was 300), or light up REALLY BIG spaces, or enable you to shoot at very small apertures so you’ve got depth of field from the end of your nose out past the formerly-accepted-as-a-planet Pluto!

SO, if you need to shoot in an office, or other brightly lit area, shooting with a studio flash instead of constant lights allows you to totally overpower the overhead lights. And I totally mean totally! Take a look at these photos. The first shot with the tungsten light at 1/50 second and f4 and the second shot with the 640 WS studio flash at 1/125 second and f22. You can’t even tell the overhead lights are on in the second photo.

1000 watt tungsten halogen lamp - 1/50th second at f4, ISO 100 - overhead lights visable

640 watt second studio flash - 1/125th second at f22 ISO 100 - overhead lights not visible

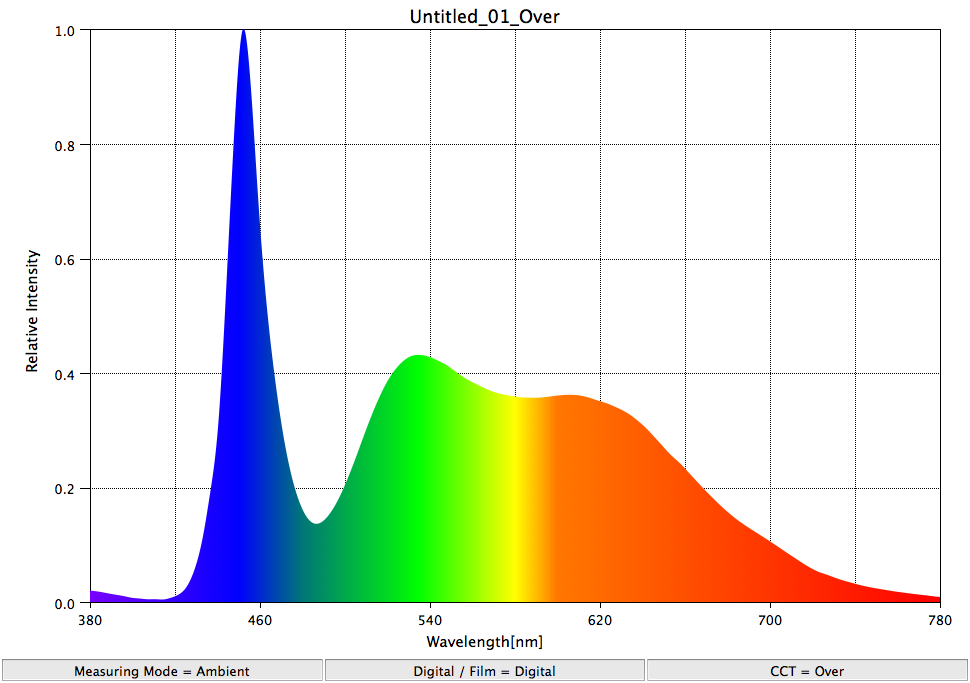

Better Light: The color rendering index (CRI) of studio flashes is higher (more like daylight, our standard here on Planet Earth) than any of the constant lights except for tungsten lights (you know, old style light bulbs, outlawed by Act of Congress, now available only in a dark alley downtown). CRI measures the relative emissions of light across the visible spectrum. Lights missing parts of the visible spectrum cannot give accurate color. Lights with excessive emissions in parts of the visible spectrum can cause certain colors to be exaggerated. Fluorescent and LED lights, on average, have a CRI from 70 or so into the mid 90’s, compared to 100 for daylight and tungsten and 99 for electronic flashes. Low CRI lights tend to make us look bad as they usually lack the warm wavelengths of light necessary for attractive complexions. Yes, if you’re the sort that loves to spend time in front of a computer monitor, you can adjust the image after the fact, but a global adjustment shifts all the colors, and a local adjustment requires careful masking.

Daylight is the standard by which other light sources are measured - CRI 99.4

Tungsten light has a smooth spectral emission, but different white balance - CRI 99.4

The best fluorescent lights cause certain colors to fluoresce - CRI 92.3

Medium priced LED arrays have a strong blue spike - CRI 92

Even inexpensive flashes are close to daylight - CRI 98.4

Short durations: Many of today’s studio lights offer action-freezing short flash durations, making it possible to capture sharp and clear photos of leaping dancers, splashing oranges and other rapidly moving objects in the controlled environment of your studio.

Photo by Janis Shetley using Edward Crim's Einstein studio flashes

Photo by Tim Farmer using Edward Crim's Einstein studio flashes.

AC/DC: Yep. They go both ways. While almost all studio flashes are designed to be powered by what our British friends call “mains”, i.e. regular household current, many of the studio flashes currently available can be plugged into portable batteries designed to power AC devices and still give a high level of performance. This makes them very useful in the field for plenty of light in UrbEx (trespassing on abandoned and decaying property) and many other applications.

Light Modifiers: Fluorescent and LED lights typically do not allow the easy employment of the wide variety of light modifiers available to studio flash users. Modifiers such as soft boxes in a variety of sizes, long throw or wide angle reflectors, grids, strip boxes, beauty dishes, snoots and Fresnel lenses. Studio flashes use a relatively small flashtube that will easily fit into many different light modifiers. Flashes also emit very little heat (unlike tungsten lamps), making it unlikely they will melt or set fire to your light modifiers. Fluorescent and LED lights are too bulky to fit most light modifiers, making it much harder to create special lighting effects.

Soft boxes in a variety of sizes and shapes for studio flashes

Reflectors, grids, barn doors, gels, beauty dishes - all easy to use with studio flashes

Umbrellas in a variety of sizes - ideal for use with studio flashes.

This is the end of this article, so if I haven't convinced you yet to buy studio flashes for the best control of your light in still photography, you must not have been listening. All I can say to that is, go back to the top and start over. Repeat as necessary until you see the light!